Best Animated Feature Film nominee L'illusionniste (The Illusionist)came out on DVD in the USA last week. I looked forward to seeing it, given that I enjoyed Sylvain Chomet's Belleville Rendezvous (The Triplets of Belleville)—who can forget that loaded, graceful scene where the men turn into monkeys?—and plenty of critics gave L'illusionniste their stamps of approval. Ten minutes in, though, I was annoyed, and by the credits, I was hopping angry. Chomet's latest has enough gender-based weirdness to rival any Disney movie.

The story, essentially, is about a past-his-prime magician who takes a young woman under his wing. How young is Alice, exactly? This is never clear, but given that she has a job cleaning a hotel/bar when they meet (Cinderella/Prince dynamic ahoy!), and that no one seems to look for her after she runs away, she seems most likely to be in her late teens or twenties. When we meet Alice, she is a textbook cliché of mousiness, to the point where She's All Thatcomes to mind.

Who's going to take off her metaphorical glasses?

The manner of their relationship is set when the titular illusionist buys Alice bright, dressy ballet flats to replace her brown work boots. Her old footwear was falling apart, but fancy, hyperfeminine shoes for a girl with a cleaning job? Really? Alice is apparently more charmed by this impractical gift than I am, and she stows away to follow him out of the country.

I perked up a little at this point; after all, Alice is proactive in fleeing her old life. Unfortunately, that may be her one decisive move, and it serves only to keep her close to her all-consuming father/savior figure. Alice is the sole character with a name, but rather than humanize her, this serves to categorize her as an object, someone people talk about rather than to. Just as experimental films like Conversations with Other Women use a lack of names to make their protagonists into everypeople, Alice's name in a sea of anonymity makes her seem important, but only as an idea. Her cheerfulness and simplicity, not to mention her housekeeping of the pair's apartment, add up to a—dare I say it?—Manic Pixie Dream Daughter.

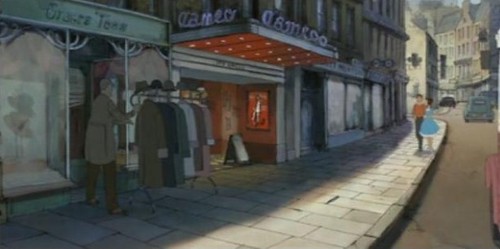

The journeys of the elder and Alice, inasmuch as they exist, are about becoming more successful and more "feminine," respectively. Alice spends an inordinate amount of the movie staring at women's clothing in store windows and asking for more gifts. This occurs in gestures rather than dialogue; like Belleville Rendezvous, L'illusionniste includes little actual speaking, which is interesting stylistically but further erases the opportunity for Alice to be nuanced. Like an old-school princess, she doesn't go to school and grows up showing scant interest in anything other than her pseudo-father and increasingly "womanly" outfits.

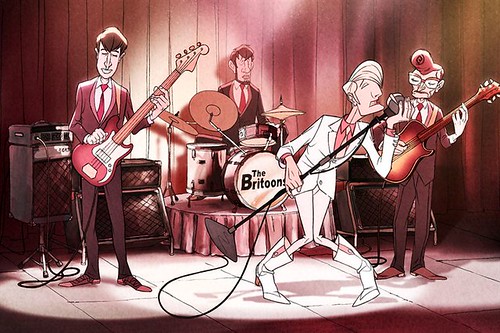

Condescension toward femininity, though, begins even in the few minutes before Alice appears:

Femmy dudes who sing. Don'tcha hate 'em?

I get it: Chomet likes to employ caricatures to make a point, and boy band members can be effeminate. These barely-characters, however, skip, giggle, and actually do that wrist-flip homophobes use to make fun of queers, and it's clearly all supposed to be hilarious. The band's legions of ecstatic female fans are drawn equally grotesquely.

**SPOILERS AHEAD!** If you're determined to watch L'illusionniste, you might want to skip the next two paragraphs.

Still, none of this prepared me for the ridiculous ending. The magician, who is now attracting reasonable-sized crowds, ignores Alice more and more, slamming doors in her face and all-around being a crappy fake dad now that he has something fun to keep his attention. Enter the new love interest, a young man who approaches Alice when she's all dolled up and smarting from that door-slamming business. She admires him first but remains passive, natch. When "Dad" spies her talking (emphasis on "spies") to another man, he packs up and abandons her immediately, leaving only a quintessentially self-pitying note: Magicians do not exist.

The Ebert Presents crew praised L'illusionniste for being "not creepy," as if that's some great feat, but the father-equals-boyfriend equation is uncomfortable and utterly unsubtle. Why is the title character acting like a betrayed husband if his connection to Alice is so innocent? What little we see of the new couple revolves around the young man fixing Alice's hair and giving her space under his umbrella, parental gestures that hammer home the message, in case someone didn't get it, that Alice Needs A Man.

How dare she?!

**END SPOILERS**

While the name of this feature has caused understandable confusion, L'illusionniste has more in common with the small, Malkovich-led film The Great Buck Howardthan 2006's The Illusionist(or that 2006 magician movie that wasn't The Illusionist). The Great Buck Howard shines in comparison, however, given that Buck's (male) assistant was A) an adult; B) a paid employee; and C) aware that his boss' demanding and possessive behavior was uncool.

Those films were all dude-focused... but then, this one is too. In the end, Alice's high percentage of screen time didn't even land her a spot on the posters:

Passed over for an ill-tempered rabbit.

And the animation? Frankly, it could not have saved L'illusionniste for me, but it's nothing we haven't seen in Chomet's previous work or Hayao Miyazaki's catalogue. Even its most gorgeous scenes, involving trains and landscapes, just make me think of the better ones in Spirited Away, an adult-friendly animated film with a strong girl protagonist.

While I've heard nothing yet about Chomet's next film, I can wholeheartedly say L'illusionniste had made my interest disappear.